Sanctuary Folk Art Gallery retires from South Division

Nine years before Grand Rapids’ first ArtPrize, Reb Roberts and Carmella Loftis were nurturing a blossoming art community in their Sanctuary Folk Art Gallery on South Division. Now, after eighteen years, Roberts and Loftis are opening a new chapter—and saying goodbye to their beloved gallery space in Heartside.

Nine years before Grand Rapids’ first ArtPrize, Reb Roberts and Carmella Loftis were nurturing a blossoming art community in their Sanctuary Folk Art Gallery on South Division. Since then, the duo have represented dozens of formerly unknown outsider artists, organized countless shows and art fairs, and have completed hands-on collaborative projects with well over 100 community and nonprofit organizations. Now, after eighteen years, Roberts and Loftis are opening a new chapter—and saying goodbye to their beloved gallery space in Heartside. “It’s time for us to make way for others to create something new,” says Roberts.

Since opening in 1999, Roberts recalls being one of a very small number of businesses operating downtown. “We were down here before Cooley [Law School], before the Douglas J. Aveda School, before all those. I think San Chez was already down here—but that was it. You could literally see tumbleweeds blowing down Commerce and Ionia.”

While many things have changed since before Y2K—ArtPrize has come to town, the Downtown Market has come to Heartside, Ionia and Commerce are now booming retail corridors—others have remained very much the same. Working with the transient and homeless population that inhabits South Division has been a daily part of Roberts and Loftis’ lives for the last nearly two decades, and while they’ve watched the rest of the city boom around them, the number of homeless, transient, addicted, and mentally ill individuals who traverse South Division on a daily basis has remained the same—if not grown.

As residents of the area, Roberts and Loftis have had a firsthand view of the nuances of the situation.

“I’ve run into hundreds of [adult foster care clients] over the years,” Roberts says. “Who actually aren’t technically homeless—but they have nowhere else to go during the day. Do they have their proper meds with them? Do they have proper clothing for the weather? Not always.”

To Roberts, the barriers that keep these individuals from receiving the housing, healthcare, and social services they need are far from insurmountable. “These are all things that can change. All these things can be addressed.”

Loftis, one of the many outsider artists whose work has blossomed under the gallery’s curation over the years, has a background in mental health advocacy, which is clearly reflected in the organizations with which she and Roberts have collaborated over the years. From Wedgewood to Mental Health Foundation of West Michigan, there are few mental health organizations in town who haven’t worked with Roberts and Loftis at one point or another.

Schools, likewise, have collaborated with Sanctuary Folk Art Gallery, as well as local churches, music festivals, foundations, art councils—the list goes on and on.

The gallery’s work, like its location, has relished in being off-the-beaten-path. Roberts defines his preferred “folk art” genre as going “beyond a lack of formal training. It’s this innate drive to create work. It’s people doing work for the people. It’s rural, it’s urban, it’s hand-painted storefront signs, it’s quilting—it’s the sidewalk of art. Everybody can walk on it.”

Folk art, Roberts says, taps into something primal in our humanity, which transcends the boundaries of style and technique that exist in more formal genres.

“Whether you think I’m an artist or not, it doesn’t matter,” Roberts says. “Call it naive, untrained, whatever. It’s as real as those ancient cave paintings. It gets the point across.”

Roberts sees the similarities and repeating patterns in the imagery of folk art across human history as no coincidence.

“Whether it’s quilting or cave paintings, those tribal images and patterns have travelled through history. There was something that was traveling through the ether. It started somewhere, and it traveled on the vehicle of common consciousness.”

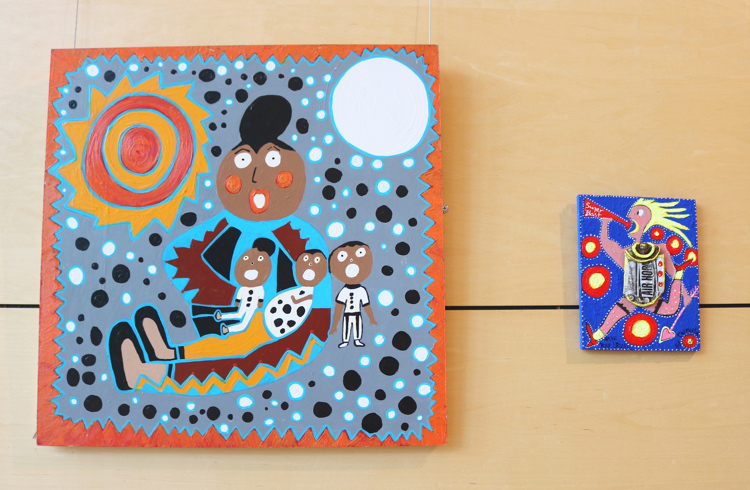

Loftis, who recently wrapped up her first solo exhibit as a Forest Hills Fine Arts Center artist in resident, offers a nearly perfect example of Roberts’ philosophy about folk art, as her work is rich with allusion, repetition, and native imagery. Some of Roberts’ work could, on the right day, be mistaken for hand-painted business signs—and it’s easy to get the sense that he kind of likes it that way.

“When you meet those [outsider artists] you’re drawn to—their vision is always different, but the drive is there. They’ll get tired, or discouraged, but they could care less about the critics.”

After closing the gallery’s doors at the end of October, Roberts and Loftis will likely find new studio space for their own work, but Roberts says they’re not likely to find another gallery space anytime soon. Roberts and Loftis’ collaboration with local organizations, artists, and art fairs, however, isn’t likely to slow down anytime soon—which means their outsider artwork, and the spirit of folk art that they’ve cultivated, will linger here in Grand Rapids for another two decades—and hopefully long after.

Marjorie Steele is a poet, journalist, publisher, and boomerang West Michigander. Currently teaching at KCAD of FSU, Marjorie’s works can be found at medium.com/@creativeonion and

Photos courtesy of Marjorie Steele of artwork by Carmella Loftis.