Invasive species and the Great Lakes: What’s happening to our beloved blue waters?

What impact are invasive species like the zebra mussel and the round goby having on the Great Lakes? And why does it matter? Author William Rapai speaks to us about his new book on invasive species in our beloved blue waters.

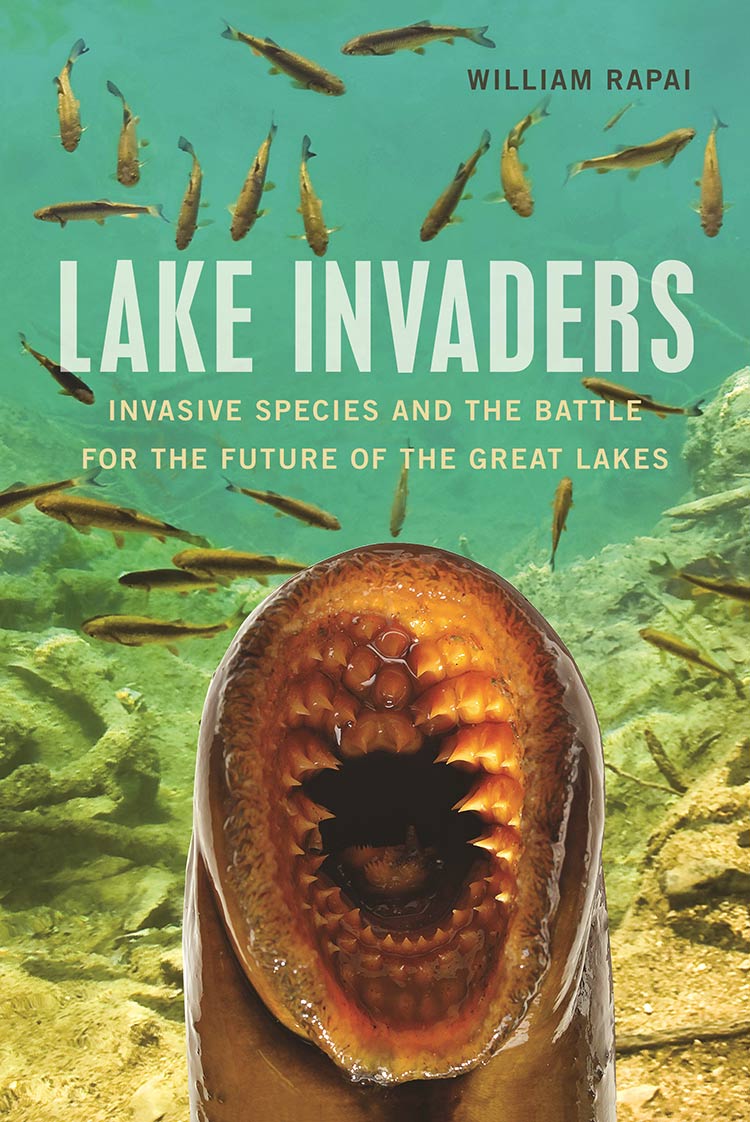

Author William Rapai is a former newspaper reporter and amateur naturalist. His first book, on the efforts to save the Kirtland’s Warbler from extinction, was named a 2013 Michigan Notable Book by the Library of Michigan. He recently published his second, Lake Invaders: Invasive Species and the Battle for the Future of the Great Lakes, which looks at the ecological upheaval caused by non-native plants and animals in the Great Lakes and the political challenges in addressing those threats.

Metromode: One of the surprising things you write about in this book is how the topic of invasive species is relatively new. You say that the term wasn’t coined until 1990, though alewives and sea lamprey have been around for in the Great Lakes for years. Why is that?

William Rapai: Humans have been moving species around the world for centuries. Think about how the dandelion came to North America. It came from Europe, probably with the pilgrims, as a food source. Only recently have we begun to see the impacts of those species moving around the world because they’ve kind of slapped us across the face.

We’ve seen it in places like Hawaii, where native bird populations have been wiped out because of snakes, mongooses and non-native birds that have been introduced. Look at places like New Zealand where native bird populations and plants have been wiped out by introduced species. It took awhile for these things to build, but when they became apparent, it was an “Oh, my god!” kind of moment.

We began to see this change in the Great Lakes with things like the introduction of the quagga and zebra mussels. We began to see how diporeia, an important plankton, was beginning to be wiped out. Wherever those mussels went, diporeia was beginning to disappear. Diporeia is an important food source for young whitefish.

You write that there’s been a cumulative effect since the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the late 1950s; that these exotic species have been coming in since then but have only gotten traction more recently. Tell us about that.

Prior to the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway, anything that made it into Lake Ontario could only make it in through the Welland Canal. That was a fairly narrow and difficult way to make your way from Lake Ontario to Lake Erie.

The Great Lakes have changed so much from their natural state already. They’ve lost so many of their original species and so many new ones have come in. So someone might wonder, what difference would a few new species make?

It matters because we are losing much of the biodiversity of the Great Lakes. We’ve lost a subspecies of the walleye, the blue pike, in Lake Erie. We’ve lost a couple of sculpin species that were important food fish for top predators. And when you begin to lose that diversity, it means that the next time the lake is stressed by some new introduced species, that lake becomes less able to fight it off. So each time something new comes in, it has an even bigger impact.

One of the interesting things you touched on in the book is that despite all the damage, some of these invaders seem to be getting integrated into the system, and some are even having positive effects. For example, the round goby eats zebra and quagga mussels. With the spiny waterflea, there are some fish that are able to eat them and depend on them as a food source.

And so when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is writing a conservation plan for that northern water snake, it has to take into account the health of the population of exotic round goby.

Alewives, which used to be a huge problem, are mostly gone?

Yes. One of the things I’m fond of talking about is the cascading effects these invasive species have had over the years. When the alewives first came in, their population in Lake Michigan alone was somewhere around a trillion fish at one time. That’s a lot of fish.

And because the alewife is gone is Lake Huron, the salmon population there has followed that decline. There’s practically no salmon left in Lake Huron, and as the alewife population continues to decline in Lake Michigan, the salmon population is also going to continue to decline there as well.

And that’s a big impact for the sport fishery?

Towns like Frankfurt and Muskegon and Ludington, where a lot of charter fishing is based, are really beginning to hurt a little bit because of the lack of people coming back from previous years. People are realizing that those fish that they used to catch, which were once so plentiful, are no longer there.

It seems that one of the big challenges is coordinating policy. I think a lot of people would be surprised to learn that states have primary authority on invasive species management, rather than the federal government.

Because there’s nothing in the Constitution that says the federal government shall have control over the Great Lakes, it becomes a matter of state control. Now, what happens when all the states surrounding the Great Lakes and the provinces of Canada have conflicting interests?

That’s what we are seeing with Asian Carp in Chicago-area waterways. You’ve got Michigan saying “No, we don’t want those carp here in our Great Lakes” and Illinois and Indiana saying “Yes, we don’t want the carp here either, but we also want to keep this canal open, because it’s a direct waterway to the Great Lakes.”

That also relates to the problem of enforcement. You talk in your book about a ship emptying ballast water that may have organisms in it, but the state of Michigan can’t hold the ship for testing.

Right. The State of Michigan has absolutely no authority to stop a ship because the federal government has authority in this matter, due to the interstate commerce clause in the Constitution.

And that means the State of Michigan and the State of Wisconsin cannot go on board a ship and seize it or stop it or tell it to stop dumping ballast water. And that limits what a state can do to protect its own water and its environment.

You’re right. And because of the federal government’s policy, the Lacey Act of 1900, we have largely been playing from behind. The Lacey Act says that harmful organisms can’t be imported into the United States. But you can only know that it is harmful after it has been here and has become established, and you can show that it is injurious to plants or wildlife in the United States. In that way, it is innocent until proven guilty.

What would you say is the biggest obstacle to taking action?

Number one, government moves slowly. It takes a long time for policy to be developed. We’ve created policymaking structures where we have to go out and talk to the public, and then we have to make revisions, and then we have to go out and talk to the public again and then we have to make revisions. The process, by its nature, moves slowly.

You can read more about invasive species and the Great Lakes in

Lake Invaders: Invasive Species and the Battle for the Future of the Great Lakes by William Rapai.This story is a part of a statewide Invasive Species Community Impact Series. Support for this series is provided by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.