Educators, mental health professionals, and food service directors are connecting the dots between good nutrition and good mental health.

This article is part of State of Health, a series about how Michigan communities are rising to address health challenges. It is made possible with funding from the Michigan Health Endowment Fund.

In northwest Michigan, educators, mental health professionals, and food service directors are teaming up to support the children they serve by connecting the dots between good nutrition and good mental health.

Paula Martin is the community nutrition policy specialist at the Traverse City-based nonprofit Groundwork Center, which provides educational activities including nutrition-based programming for an array of partners including the Traverse Bay Area Intermediate School District (TBAISD). She cites studies that have proven that with the simple introduction of school breakfast programs, students improve academic performance, stay more focused during instruction, and have fewer behavior problems, better attendance, less tardiness, fewer trips to school nurses, and increased graduation rates.

“Nutritional psychiatry is an emerging field,” Martin says. “As we help to improve diet quality, we are helping to calm the brain. If children’s baseline nutritional needs are not met, they are already starting at the bottom of a well.”

Groundwork Center staff see farm-to-school projects and school-based meal programs as a way to address adverse childhood experiences and build resilience through a model that considers children’s wellness in terms of diet, mental health, exercise, body composition, sleep, and brain function.

“Kids that have experienced trauma early in their lives have very low patience when they experience hunger. You have to have a snack ready. The time it takes from stove to table could be serious meltdowns,” Martin says.

Programming for behavioral health and nutrition

Northwest Michigan providers have established a variety of programming to bolster kids’ behavioral health and nutrition in schools. The Health Department of Northwest Michigan (HDNM) has established child- and adolescent-based health centers within Alanson, Boyne Falls, Central Lake, Charlevoix, East Jordan, and Ellsworth public school districts. In addition to the traditional school nurse, these centers provide children primary care, vision and hearing screenings, health education, behavioral and developmental health screenings, and mental health care.

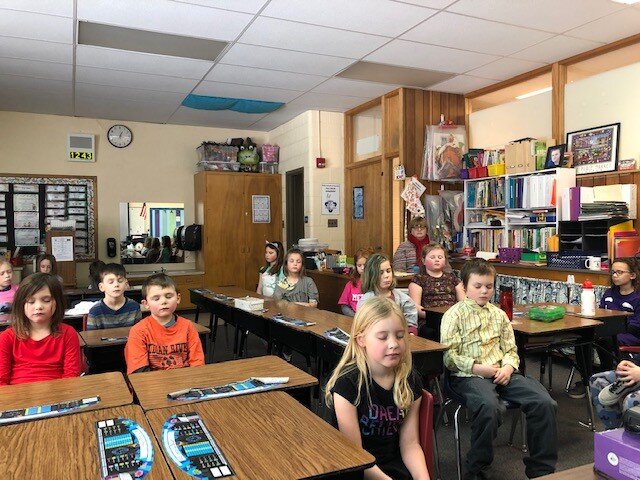

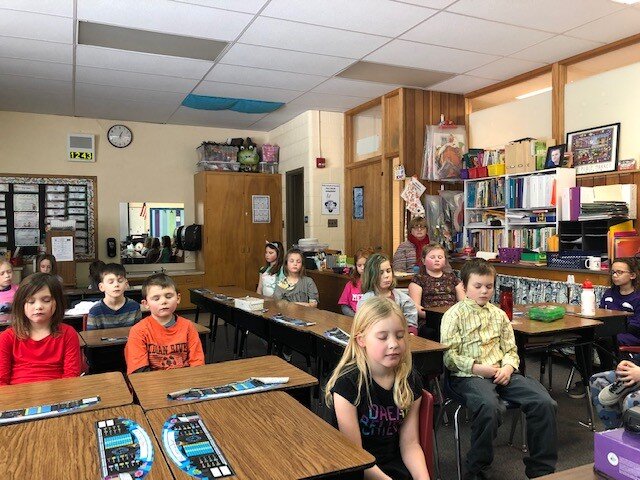

In Otsego, Antrim, Charlevoix, and Emmet counties, behavioral health staff have also introduced the evidence-based Mindful Schools curriculum into the classroom. Teachers lead students through simple mindfulness exercises during 15-minute sessions taught twice a week for eight weeks.

“They might help the students do a ‘mindful minute,’ to pay attention to what’s happening in their surroundings and in their minds [and] to notice the feelings they are having,” says Lynne DeMoor, HDNM community health coordinator and nutritionist. “One thing kids tell us is that it helps them to calm themselves down and not get upset about things.”

Another exercise is called the “hot cocoa breath.” Kids are encouraged to imagine having a cup of hot cocoa that is too hot to drink. While waiting for it to cool, they slowly inhale through their noses and savor the delicious aroma, then exhale slowly through their mouths to cool the cocoa down.

“Kids learn to use techniques like that in heated moments. They remember, ‘We could do a hot cocoa breath right now,’ and know that it does help them to feel better,” DeMoor says. “We also teach them a lot about feeling sensations in their body that indicate emotions — shoulders creeping up to the ears, clenching their teeth, hands in a fist — to recognize those signals in their bodies and know what they might mean and resolve them before something boils over.”

Children as young as second grade have shared that the techniques have helped them stay focused at school and fall asleep more easily at bedtime. Teens can practice mindfulness to replace negative thoughts or peer comments with self-compassion. And teachers have reported having more teachable minutes. When the classroom shows signs of erupting into chaos, teachers lead their students in taking a mindful minute to help them rein in their behavior.

“Teachers like to use it during transitions, like when kids are coming back to class after lunch recess,” DeMoor says. “Another important part of the curriculum is learning gratitude and kindness and being able to develop their own acknowledgment of things they are grateful for, [such as that] you saw your favorite color, or the fresh air you’re breathing. Finding those ways to be grateful helps us to be softer on ourselves.”

Brain foods boost smarts and good behavior

According to DeMoor, healthy eating is equally important to students’ behavioral health.

“You’ve heard the expression ‘hangry.’ There’s a really direct effect,” DeMoor says. “First and foremost, our brains depend on a steady supply of blood sugar for energy. Other body systems can convert fat or muscle to energy, but not the brain.”

That’s not to say any old food will do the trick. Healthy blood sugar levels are created by foods like nuts, seeds, leafy green vegetables, berries, and legumes. DeMoor explains that 95% of the serotonin the brain’s neurotransmitters rely on is created in the gut during digestion.

USDA Farm-to-School grants fund HDNM’s “Try It Tuesdays” program in Petoskey Public Schools, which feature locally grown food in classroom taste testings. Students vote “tried,” “liked,” or “loved” after tasting the foods. When a food gets an abundance of “loved” votes, the food services director adds it to the lunch menu rotation.

TBAISD has both Farm-to-School programs and SNAP-Ed programs in many of its schools, as well. Some schools have garden beds or hoop houses that may be the site of nutrition lessons, taste testings, Michigan Harvest of the Month activities, or cooking expositions.

“We do a lot of nutrition work with the schools,” says Marshall Collins, TBAISD instructional service consultant for school health and social services. “We also work with the school and the community to try to support policies, systems, and environmental changes so we are not just doing the lessons but trying to create a change within the system.”

Collins agrees that strategies like mindfulness and trauma-informed approaches further help kids with achieving better behavioral health.

“It plays into that whole-child approach. So many things affect the child’s behavior over time – … the way kids behave, the way kids eat, and the way kids learn. We can help if we take some of these things off their plate,” Collins says. “Nutrition is easy. You just provide better nutrition within the school system so kids feel better. Our kids are being exposed to different vegetables and fruits, learning how to watch their calories, learning how much to put on their plate and not to overeat. We as adults get irritable when we don’t eat. Imagine being a kid.”

We achieve what we eat

While academics have always been about brain power, emerging tools like mindfulness and acknowledging nutrition’s role in behavioral health give more children the ability to achieve academic success and feel happier while doing it. Collins says schools too often expect excellent work from students without considering how well they’re doing in their lives outside of school.

“We don’t know if that student had a healthy breakfast. We don’t know if they had the right amount of right sleep. We don’t really know what’s going on in their lives,” he says. “The first thing we focus on is our priority, which in reality, our priority should be the kids. We need to make sure they are taken care of.”

A freelance writer and editor, Estelle Slootmaker is happiest writing about social justice, wellness, and the arts. She is development news editor for Rapid Growth Media and chairs The Tree Amigos, City of Wyoming Tree Commission. Her finest accomplishment is her five amazing adult children. You can contact Estelle at Estelle.Slootmaker@gmail.com or www.constellations.biz.

Buckley School/Community Garden photo courtesy of TBAISD. Mindfulness photo courtesy of Health Department of Northwestern Michigan. All other photos courtesy of Groundwork Center.