Zen and the Art of Krav Maga

Ruth Terry tries Krav Maga, a tactical self-defense system invented in the 1930s by Imi Lichtenfeld, a Jewish Slovakian who sought a way for the Jewish people to defend themselves against Nazis. This effective combat technique is being taught in West Michigan today.

About a month ago, my workout buddy Matt suggested we try something called “krav maga.” Well into my annual Star Trek marathon, I imagined krav maga as a cross between Klingon bat’leth training and Zumba.

?For once, my vivid imagination wasn’t too far off. Close quarters combat and maniacal jumping about were indeed the first things I noticed when we caught a krav maga class at West Side Fitness a few weeks later.

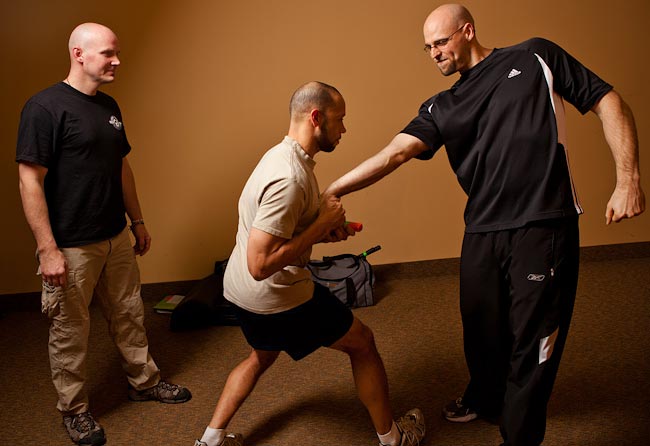

Instructor Craig Gray ran two students through a mash-up of high-speed drills. They darted and pushed, kneed and charged and, every time Gray sounded his whistle, dropped and gave him 10.

Matt and I watched from a corner, waiting for our own demo class to begin. He was totally into it. I was secretly horrified and prayed Gray wouldn’t make me do push-ups.

Street Fighting Man

Krav Maga was created in the 1930s by Imi Lichtenfeld, a Jewish Slovakian, to counter Europe’s increasing anti-Semitism. Lichtenfeld, whose father was a police officer and athlete, parlayed his own boxing and wrestling experience into a tactical self-defense system that could respond to actual threats his students faced.

“Back then the Nazis would travel around and make examples of Jewish people, beat them up and do stuff to their businesses,” Gray says. “As the violence started ramping up, he and his father started training the Jewish community to defend themselves against folks who were sympathetic to the Nazi cause.”

Lichtenfeld fled to Palestine in 1940, where he taught Krav Maga to Israeli paramilitary groups for the next four decades. In 1981, he opened training up to instructors from other countries.

Krav maga soon became popular for training law enforcement and military worldwide because, unlike other martial arts, it is easily adapted for different situations.

“Our global society has changed the way we do warfare. It’s not ‘us versus them’ anymore. You don’t always know who the enemy is,” explains Gray. “Krav continues to change to embrace new threats.”

Weapon of Minor Destruction

No matter the situation, Gray believes “going physical should be a last resort.”

“The idea of the way we teach is protection of self and others. If we can train to do with less force, it’s less damaging for us,” says Gray. “Frankly, I’m protecting the bad guy.”?

This offers more than just physical protection; it prevents psychological fallout. According to Gray, except for the four percent of people who are sociopaths, all humans must justify their actions. Violence requires us to “separate” and dehumanize — an immediately effective, yet ultimately volatile workaround that can eventually lead to post traumatic stress.

“It’s not like a video game,” says Gray, who is also a conflict resolution expert and adjunct instructor of warrior ethics for the Homeland Security and Protective Services Academy within Gerald R. Ford Job Corps.

“When you realize that these are human beings and you cannot justify your actions as protection of another person or just doing your job, there are a lot of post traumatic and emotional elements that come about after the fact.”

But Gray’s philosophy isn’t the only one. West Michigan Krav Maga instructor Tony Danielski advocates doing whatever it takes — even “biting, punching, and gouging” — to protect yourself and your family, regardless of the risk to an attacker.

“I’m not warm and fuzzy,” says Danielski, a kung fu expert and martial artist since age 9. “I teach a very violent, straight to the point way of subduing them and getting rid of them. I don’t coddle anybody.”

Though Danielski admits he’s “not the krav maga instructor for everybody,” his no-nonsense approach seems to resonate with students. In the seven years he’s been teaching, he’s never wanted for business, consistently drawing everyone from librarians to military personnel.

Keep it Simple

Gray and Danielski might not appear to have much in common — even their websites contrast starkly — but they both agree about what sets Krav apart from other martial arts.

“When I started Krav Maga I was like, ‘wow, it’s so simple,'” Danielski says. “I never knew defending myself could be so easy.” He sums up with characteristic candor: “You take the best of martial arts and filter out the useless techniques.”

“A lot of people don’t want to take 30 years of their life to learn a martial art,” admits Gray, 40, who actually has 30 years of martial arts experience under his black belt. “You can learn Krav in a relatively short amount of time. Sometimes, I’ll teach cops something in the afternoon that they use that night in the field.”

All this bodes well for folks like Matt and me: pragmatic types with short attention spans.

A mere 10 minutes into our demo class, Gray has already taught us a handful of basic motions to mix and match for different threats. Fifteen minutes later, I can parry Matt’s rubber knife blow.

Learning the moves is simple. Conditioning your body to instinctively produce them under duress? Not so much. The cold, hard truth is that unless I’m attacked head on, in broad daylight, with a bright orange weapon, I probably won’t reproduce anything close to the right response. Heaven forbid someone tries to stab me when I’m in heels.

Fortunately, Gray lets students learn the skills they need at their own pace. Some just want a few quick and dirty tips. Others work their way up to the ultimate challenge — the Shark Tank. This rigorous assessment tests students mentally and physically. They run a gauntlet of “real life” verbal, physical, and faux weapon assaults. And they do it all with their eyes closed.

“You want to get to that — not to sound cliché — Zen state when you can react to whatever comes at you,” Gray explains. “If you’re thinking about it, it’s too late. You’re thinking about the technique, not the situation.”

For the Health of it

Hand to hand combat skills and tiger-like reflexes aren’t the only reason to do Krav Maga. High-impact krav workouts helped insurance agent Marc Specter win a lifelong battle with his weight.

“I joined the class because I was on a weight loss crusade,” says Specter, who has been doing Krav Maga on and off for 6 years. “My personal goal was to lose weight and gain a skill. It just seemed like the time to engage.”

Specter admits he was “initially turned off” to martial arts.

“I couldn’t even jump rope,” he remembers. “I was never really the athletic type.” At 6’4″ and 300 lbs., he was most afraid of falling down. But he stuck with it, and with Gray’s support, eventually lost more than 100 lbs. Today, he assists Gray as a class facilitator.

Defend Yourself

Despite krav maga’s obvious benefits, people still opt out. I’m even reluctant to join Matt when he starts classes. As a former roller derby blocker, I’m not bothered by the physicality. So what’s my problem?

Gray says this kind of reaction is common. Learning self-defense scares people because it makes danger seem more real.

So do statistics. FBI data shows that Grand Rapids has more than five times as many violent crimes per square mile than the national median, and that 1 in 97 of us will become victims of violent crime. Ironically, getting killed, robbed, or assaulted is actually twice as likely to happen than a car accident — something most people are insured for.

“Not knowing is that safety blanket,” says Gray. “If I don’t know, then I don’t have to acknowledge that there’s a problem.”

But ignorance is not necessarily bliss.

“If you don’t do anything that means that someone else is resolving the situation for you,” Gray cautions. “The situation will be resolved either for you or by you.”

Ruth is a freelance writer and fundraising consultant living in East Hills. She enjoys world foods, travel, crafts and those BBC ocean documentaries. Ruth also has very curly hair.