Do Good: Servants Center helps mentally ill homeless get off and stay off the streets

With budget reductions in state and federal programs that support vulnerable families, it's difficult for low-income and homeless residents to access the mental health care they need. Victoria Mullen reports on Servants Center, one local organization that helps those struggling with mental health issues get vital treatment.

It’s hard enough to be a relatively healthy homeless person struggling to survive, but imagine what it’s like to be homeless and mentally ill.

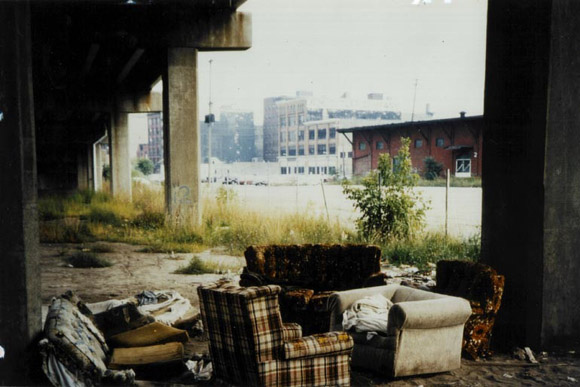

As you stroll down to Heartside for lunch at God’s Kitchen, you meet up with some friends and find some comfort and camaraderie. Then it’s back to the streets. You have maybe eight hours to go before dark when you can safely return to your shelter under an abandoned porch — safety being relative, of course. But how to kill all that time?

Maybe you gather on a corner with your peers. Perhaps you panhandle for some cash to purchase a beer. Overcoming boredom is hard work. Drivers passing by ignore your sign and pass judgment as you drink your beer. Never mind that many of those same people will crack open a cold one or few when they get home from work. Different rules for different folks.

Lately, you haven’t been feeling so well, and the voices are back. Because you’re on SSI, your income is too high to qualify for Medicaid. You don’t know how to manage your money, so you never seem to have any. Without insurance, you can’t get your antipsychotic med prescription refilled, so you rationed your pills. You ran out of meds a few days ago, and now you’re feeling unbalanced and bewildered.

Going to a homeless shelter is not an option. The last time you tried checking into one, a shelter staff person drove you away. He didn’t understand that you had to cut in and out of the supper line because the U.S. Army was communicating important messages to you from a specific brick in the wall, and you could only hear them when you put your ear close by. You weren’t even cutting in front of anyone.

And so, you wander your days away, lost, hungry, and confused. The voices get louder. You’re becoming unhinged, and you yell at the voices to shut up. To the untrained eye, you appear drunk or stoned. People cross the street to avoid you.

You are a pariah.

Since 1993, Servants Center (SC) has reached out to help the mentally ill homeless in Grand Rapids get off and stay off the streets. Over the years, SC has served over 1,500 individuals or families in homeless crisis situations.

“People suffering from untreated mental illnesses often do not function well in homeless shelters,” says Patrick Cameron, executive director of Servants Center. The ministry offers case management and other services to the homeless, like finding housing and employment.

“Shelters must have rules, but many mentally ill homeless people have disorganized thinking that impairs their ability to understand and comply with rules,” Cameron says. “Staffers don’t always recognize schizophrenic delusions, and they don’t realize someone is mentally ill. So, they throw them out or call the police.”

According to the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI), 40 percent of chronically homeless people in America suffer from some type of serious mental or neurological brain disorder.

Until recently, local mental health agencies like Network180 provided case management services for the mentally ill. But then things changed. When Michigan implemented “Healthy Michigan,” a part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), on April 1, 2014, hundreds of thousands of Michigan citizens gained access to health insurance, many for the first time. Michigan’s working poor now have access to low-cost health insurance through the state’s new Healthy Michigan Plan.

But funding for mental health services is being diverted to other areas. After years of declining investments, the Department of Human Services (DHS) budget signed by the governor for the year beginning October 1, 2014, further reduces total funding by 4.8 percent, from $6.05 billion to $5.76 billion. Driving the reductions has been an unprecedented drop in the number of families with children able to access income assistance through the state’s Family Independence Program. Source.

Funding for State Disability Assistance has decreased 22 percent in five years. Reductions in caseloads and spending partly reflect policy decisions that have made fewer families and children eligible for public assistance benefits, including lifetime limits on income assistance, and a new asset test for food assistance. Decisions made by the legislature will affect nearly 2.4 million Michigan residents—including over 1 million children—who receive some form of public assistance to help them hold low-wage jobs, feed and shelter their children, access health care, or survive when faced with serious illnesses or disabilities. Source.

In a column for Dome Magazine, president at National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Metro, Leon Judd wrote: “As a result of the reduction in the [General Fund], we are seeing [Community Mental Health Centers] and networks announcing program and service reductions, service terminations to consumers and the list goes on. Let there be no mistake, this is a financial catastrophe and it could have been avoided had the powers that be been more patient before trying to affect savings from the State of Michigan as a result of Healthy Michigan enrollment.” Source.

The upshot: Once the money runs out, services like case management will no longer be offered or reimbursed by places like Network180, an organization that connects individuals and families to services for mental illness, substance abuse, and developmental disabilities.

People under case management for years have had their benefits abruptly cut off, without notice. Servants Center picks up some of the slack, but they are bursting at the seams with requests for help. There are only four people on staff.

“We serve as Social Security Representative Payee for hundreds of mentally disabled persons,” Cameron says. “We also serve as Kent County Probate Court Guardians.”

So, here we are, fifty years after President Johnson’s State of the Union speech announcing a “War on Poverty,” and 15 percent of the U.S. population – that’s 46 million people – are living below the federal poverty line. Source.

According to the 2014 Poverty Rate in Kent County Fact Sheet, poverty in Kent County increased in 2012 to 16.8 percent from 14.7 percent in 2011. As of May 2013, Michigan’s median income is down by 20 percent and poverty overall was up 66 percent. Our state ranks in the top 10 nationally for the number of people without jobs.

Despite these setbacks, Grand Rapids is making some progress in its quest to end homelessness. In 2004, the Grand Rapids Area Housing Continuum of Care (GRAHCOC), along with other agencies and organizations, published a document, “Vision to End Homelessness.” The goal: to end homelessness by the end of 2014. Progress is illustrated by the following, but is in no way limited to these examples.

The Salvation Army Booth Family Services now oversees the Housing Assessment Program (HAP), the central intake for individuals in a housing crisis – such as foreclosure, domestic violence, and eviction – in the Grand Rapids/Kent County area. In 2009, the central intake function was expanded. Currently, HAP provides referrals to over 24 programs at 13 organizations.

Dwelling Place, 101 Sheldon Blvd. SE, has expanded the number of income-based housing units available in Grand Rapids and some surrounding areas. It currently offers 380 permanent supportive housing units across West Michigan for households who have trouble getting and maintaining affordable housing. According to the agency’s 2012 Annual Report, Dwelling Place owned or managed 1,296 affordable units in 30 housing communities in 2012.

According to the report, “Live/work apartments created by Dwelling Place along Division Avenue since 2004 have served as a catalyst to encourage many arts-related businesses and events to locate in the immediate vicinity. Martineau, Kelsey, and Verne Barry Place Apartments feature numerous ‘Live/Work’ spaces for over 62 low- and moderate-income artists. Many of these occupants also operate businesses from their residence.”

And then, there is Well House, which uses the National Alliance to End Homelessness (NAEH) “Housing First” model. Thanks to grantors like the Kellogg Foundation, in the past couple of years, Well House has purchased and rehabilitated several inner city houses that were slated for demolition. The most recently rehabilitated house, at 239 Sycamore SE, is now home to two formerly homeless families.

Get involved:

– Volunteer and/or donate to Servants Center.

– Keep up to date with what’s going on at Servants Center.

– Keep tabs on Well House, donate, and volunteer.

– Learn about StreetReach.

– Learn more about Network180.

– Learn about the housing voucher program.

– Read the National Survey of Programs and Services for Homeless Families from the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

Here’s a list of some other organizations that need volunteers and donations:

Access of West Michigan

Catholic Charities of West Michigan

Community Legal Services

Degage Ministries

Dwelling Place

Family Promise of Grand Rapids

God’s Kitchen

Goodwill Inc.

Grand Rapids Red Project

Guiding Light Mission

HealthNet

Heart of West Michigan United Way

Heartside Business Association

Heartside Gleaning Initiative

Heartside Ministry

Mel Trotter Ministries

Street Reach/Pine Rest

Download a pdf of places that need donations and volunteers.

Images courtesy of Servants Center and Adam Bird Photography.