School Is Out? Hold Those Wrecking Balls For A Minute

Local Catholic church officials have their sights set on demolishing Saint Andrew’s School in downtown Grand Rapids. But some have their sights set on a bigger picture.

A guest editorial by Elizabeth Hoffman Ransford

If you lived in Grand Rapids during the 1980s and 1990s, chances are you have heard of St. Andrew’s School, an inner-city Catholic school dedicated to cultural diversity and academic excellence — as they liked to say, “a miracle in the heart of Grand Rapids.”

Today, the St. Andrew’s school building is under threat of demolition to complete the $22 million “Cathedral Square” development promoted by the Catholic Diocese of Grand Rapids. Recently, the Historic Preservation Commission voted to recommend the creation of a study committee to evaluate the historic significance of the school. Last week, the City Commission voted to consider this proposal at a joint meeting with the Planning Commission on March 22, when both commissions will invite public comment on the issue and vote on a possible moratorium on demolition.

I will be there on March 22 to speak against the demolition of St. Andrew’s School.

I believe that the St. Andrew’s School building should be saved. While I have powerful memories about my own experience attending St. Andrew’s in the 1980s, this issue is not about personal nostalgia. Instead, the demolition of St. Andrew’s School raises much bigger issues about the preservation of our city’s cultural heritage, about fiscal and environmental responsibility and finally, about creating an urban vision to guide downtown Grand Rapids into the rest of the twenty-first century and beyond.

Historic buildings are our collective cultural heritage. They give richness to the fabric of our landscape; they create a sense of place that anchors our community with a clear identity over the passage of time. Buildings matter! Once a building is gone, we can never get it back. Anyone who has ever flipped though the book Grand Rapids: Then and Now recalls the visceral realization of this fact.

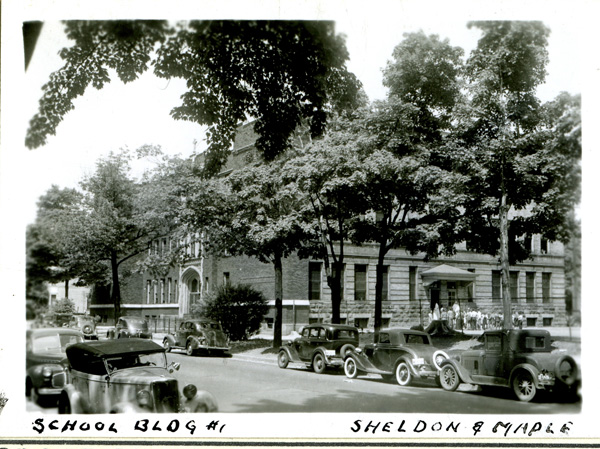

St. Andrew’s School, built in 1874, is the oldest school building in Grand Rapids. It has survived two fires, one in 1899 and one in 1915. Its presence reminds us of the vibrant residential neighborhood that used to exist around Sheldon Blvd. and Maple St. Father McGee, the historian of the Catholic Diocese, writes that “great numbers of Irish Catholics had moved into the location…forming an almost solidly Catholic community.” Around the school, houses and businesses mingled together on tree-lined streets. Today, nearly every remnant of this residential community has been razed, leaving only St. Andrew’s as a reminder of the area’s history.

From an economic development perspective, used buildings are more productive and more profitable than empty space: they create economic activity and add to the tax rolls of the city. Look at the Boardwalk Condominiums, created out of the old Berkey and Gay Furniture Factory. A decade ago, people who wanted to demolish this complex delivered the same rhetoric that we are hearing now about St. Andrew’s School: the building is an eyesore, it has outlived its usefulness, its rehabilitation would be cost prohibitive. Ten years later, the Boardwalk Condominiums have almost single-handedly revived the near north side, even in these difficult financial times.

Furthermore, nothing is greener than an existing building. Repurposing an existing building saves resources: the financial resources that would be used to raze it, the material resources in the building that would end up in a landfill, the other financial and material resources that would be needed to build a new building in its place someday. Does it make financial sense to throw away a good building?

We’ve been down this road before. In the 1950s and 1960s, city planners across the United States thought that modernizing the city meant tearing down old buildings to leave lots of room for parking lots and cars. But what these demolitions actually created was a space without people, a space without visible landmarks to denote a historical past — a dead space. People stopped going downtown, because there was nothing there to go to. Today, downtown Grand Rapids is attempting to recover from planning decisions like these by making an effort to preserve and reuse historic buildings, creating a density of commercial attractions and residential options, and integrating new modern buildings like the Art Museum into a more robust urban fabric.

St. Andrew’s is a short walk from downtown. In a few years, this area could be an important element in an expanded and even more vibrant urban center. Instead, the diocese’s plans show a small “green space” created by the school’s demolition, surrounded by acres of surface parking. This plan resembles nothing more than the parking lot of a suburban shopping mall — an environment that has no respect for time and place has little respect for people, however suitable it may be for the parking of cars.

The best city planning theories of today agree that welcoming spaces presuppose density of people and a density of interaction, with places to go and things to see. What we need in downtown Grand Rapids are more intensively used spaces, not fewer.

Why not renovate the school for senior housing, as some people have proposed? Today, many seniors are looking for residences that allow for increased mobility. The St. Andrew’s School building is close to downtown, close to transit lines, close to medical services and close to a church, making it an ideal site for such a reuse.

Don’t demolish a perfectly usable building for the sake of demolishing a building. I hope that the Diocese — which has already invested so much money in the Cathedral Square project — may be convinced to consider alternatives to demolition, alternatives that will preserve the building for future uses to benefit St. Andrew’s parish, the Diocese of Grand Rapids and the urban vitality of downtown Grand Rapids.

[McGee quote: John W. McGee, The Catholic Church in the Grand River Valley, 1833-1950 (Lansing, Mich.: Franklin Dekleine, Co., 1950), 190.]

After Elizabeth Hoffman Ransford graduated from St. Andrew’s School in 1991, she went on to complete a doctorate in American History and Public History at Loyola University Chicago, with a dissertation that focused on the place and uses of sacred buildings in the context of the wider community. She and her husband, Charlie, moved back to Grand Rapids from Chicago in 2010 to renovate a house in the Fairmount Square Historic District.

Photos in order:

Elizabeth at the Sistine Chapel

Saint Andrew’s School today

Saint Andrew’s 1936

Saint Andrew’s School today

Aerial of Saint Andrew’s School and the Cathedral, 1940

Site plan of the proposed plaza, post demolition