Cleaning up West Michigan’s ‘Areas of Concern’

Once West Michigan's most contaminated waterways, the White Lake and Muskegon Lake Areas of Concern are making their way toward recovery.

West Michigan may have a reputation as a water wonderland, but there have been some dark spots along the way as a result of historical contamination. We took a look at how west Michigan’s two “Areas of Concern” became polluted, and how they are making a comeback.

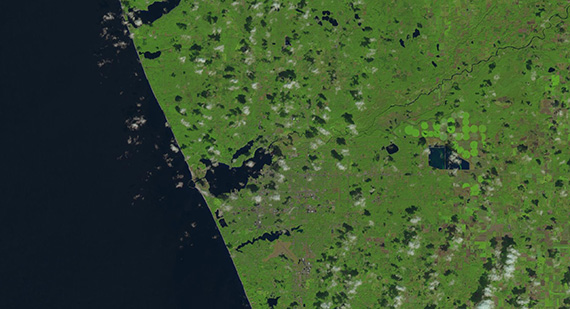

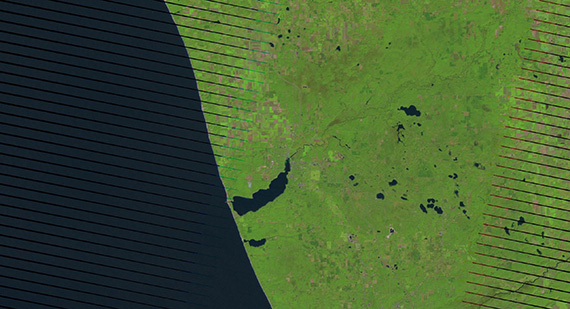

Map data source: USEPA. Acquired with the assistance of ECT Inc.

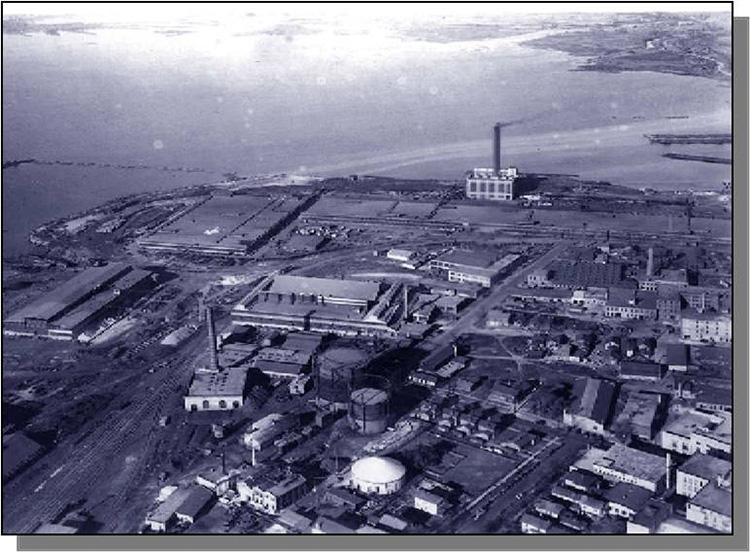

Muskegon Lake Area of Concern

Muskegon Lake is a 4,149 acre inland coastal lake in Muskegon County, Michigan along the east shoreline of Lake Michigan. The Muskegon Lake Area of Concern (AOC) includes the entire lake; the lake is separated from Lake Michigan by sand dunes. The Muskegon River flows through the lake before emptying into Lake Michigan. Additional tributaries include Mosquito Creek, Ryerson Creek, Ruddiman Creek, Green Creek, and Four Mile Creek.

In 1985, Muskegon Lake was designated an AOC for several reasons. Water quality and habitat problems associated with the historical discharge of pollutants into the AOC were a major contributor to the lake becoming an AOC. In addition, high levels of nutrients, solids, and toxic contaminants entering the lake had caused a series of problems. Together, these issues resulted in nine beneficial use impairments for the lake, four of which have been removed:

- Beach closings – REMOVED 2015.

- Restrictions on fish and wildlife consumption – REMOVED 2013.

- Eutrophication or undesirable algae (in Bear Lake, which feeds into the north end of Muskegon Lake)

- Restrictions on drinking water consumption, or taste and odor – REMOVED 2013.

- Degradation of fish and wildlife populations

- Degradation of aesthetics

- Degradation of benthos

- Restrictions on dredging activities – REMOVED 2011.

- Loss of fish and wildlife habitat

“The work that has been done in the Muskegon Lake AOC began in the early 1990s with a group of very dedicated volunteers,” says Kathy Evans, environmental program manager for the West Michigan Shoreline Regional Development Commission and long time activist with the Muskegon Lake Public Advisory Council. “We strove over many decades to involve the greater community until we formed a watershed group that really was reflective of the greater community. That group over the last decade has really pulled together and done the serious planning and identified the projects that are needed to get the AOC delisted. We’ve been really fortunate over this last decade to have funding finally to actually realize those goals and dreams to clean it up and restore habitat.”

That group is the Muskegon Lake Watershed Partnership (MLWP), now the public advisory council for the AOC, made up of several state and local organizations. The group was instrumental in developing restoration targets for the AOC and helps monitor progress on work being accomplished. The Partnership has provided funding to facilitate much of the work in the AOC and has provided a match for Great Lakes Restoration Initiative projects.

“They’re like my poster child of how to do it right,” says Sharon Baker, AOC coordinator for the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. “They’re already looking at what they’re going to do after they delist. They want to keep eyes on the AOC projects – whether it’s sediment cleanups or habitat restoration – to make sure that they don’t fail or that somebody doesn’t come along and disturb things.”

In 2006, shortly after the Great Lakes Legacy Act (GLLA) was authorized to clean up areas in the Great Lakes with contaminated sediments, the Ruddiman Creek Legacy Act cleanup was completed in which 90,000 cubic yards of contaminated sediment were removed. The Clean Michigan Initiative bond program was used as a match for the project.

“If we didn’t have the Great Lakes Legacy Act, I don’t think the community would have ever seen that this magnitude of restoration was even possible,” says Evans.

In 2008, a Muskegon Lake Area of Concern Fish and Wildlife Habitat Restoration and Beneficial Use Impairment Removal Strategy was developed. The document lays out restoration plans for four focus areas within the AOC that guides work needed to remove the “loss of fish and wildlife habitat” and “degradation of fish and wildlife populations” BUIs.

The Muskegon Lake Stage 2 Remedial Action Plan, developed by the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality in 2011, identifies actions needed to restore all of the AOC’s impairments. It is also a tool for documenting and communicating restoration progress.

In 2011, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged the navigation channel of Muskegon Lake. This, in effect, removed the “restrictions on dredging” BUI.

In 2012, a $12 million project under the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative’s Legacy Act removed about 43,000 cubic yards of sediment contaminated with mercury and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs, from the lake’s Division Street Outfall. A 60-acre cap was placed over the area to contain any remaining pollution. Nearshore habitat restoration was also completed at the same time.

Following this work, in 2013 the “restrictions on fish and wildlife consumption” and “restrictions on drinking water consumption BUIs were removed. In 2015, the “beach closings” BUI was removed primarily due to illicit sewer connections in the Ruddiman Creek area being addressed.

In February 2015, the MLWP hosted a meeting with EPA, DEQ, and local officials where they jointly reviewed remaining BUI removal projects and came to agreement on a list of priority management actions needed for delisting the AOC.

The next area to be cleaned up in the AOC is Ryerson Creek, which should take place in the late summer or fall of 2016. A public/private partnership is hoping to continue using GLLA funds to remediate contaminated sediments in the mouth of Ryerson Creek as well as at the Zephyr Fire Suppression Ditch. Landowners, city officials and developers have expressed strong interest in cleaning up the bay and in restoring habitat and related aesthetics.

“The community owns these projects,” says Baker. “They take a lot of pride in it. It’s amazing how many people are involved because of the good work that the Partnership does in outreach and celebrating successes when they remove a BUI.”

Partners working in the Muskegon Lake AOC are hoping to delist the AOC by the end of 2018. To do so, the remaining five BUIs must be removed.

“We’ve already seen a lot more development plans for more public outdoor recreation on Muskegon Lake because of the cleanup work that we’ve done and especially because of the shoreline habitat work that we’ve done,” Evans says. “We really cleaned up the shoreline.”

In addition to completion of AOC delisting and related management actions, the MLWP plans to continue working with the DEQ and other state and federal partners to address priorities to protect the Muskegon Lake watershed ecosystem into the future.

White Lake Area of Concern (now “delisted”)

White Lake is in Muskegon County along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. In 1987, it was declared an Area of Concern (AOC). The area was highly degraded because of contaminated surface water and groundwater, wastewater and sewage. The White Lake AOC was delisted in 2014.

There were eight beneficial use impairments (BUI) that had to be addressed and removed before the AOC could be delisted. The following is a list of those BUIs along with the year in which they were removed:

- Restrictions on Dredging Activities – REMOVED 2011.

- Eutrophication or Undesirable Algae – REMOVED 2012.

- Degradation of Benthos – REMOVED 2012.

- Restrictions on Fish and Wildlife Consumption – REMOVED 2013

- Loss of Fish and Wildlife Habitat – REMOVED 2014.

- Degradation of Fish and Wildlife Populations – REMOVED 2014.

- Restrictions on Drinking Water Consumption and Taste or Odor Problems – REMOVED 2014.

- Degradation of Aesthetics – REMOVED 2014.

Much of the work accomplished to restore and delist the AOC was due to efforts of the White Lake Public Advisory Council (PAC). The PAC, a formal council of members from throughout the White Lake area, worked to provide the public with information, services, and projects to improve the environmental quality of White Lake and its affiliated watersheds. The PAC advised agencies, expressed views and voiced the concerns of the local community.

One long-time member of the PAC and the White Lake community, Tanya Cabala, sees the delisting of White Lake as a shining example of success in her lifetime.

“I think what it means for the community is the beginning of a new era,” she says. “We have been focused for over 25 years on cleaning up problems from the past and now it’s time to look forward with a clean slate with a lot of exciting opportunities. People are very happy about the clean up and the delisting. It’s like ‘Wow! How cool that my community was able to do this. It’s just a fantastic thing and hope we can inspire other communities to do the same thing.”

John Riley, AOC coordinator for the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, says it’s important to stress that although the Area of Concern designation is gone, it doesn’t mean it’s the end of all the environmental, water quality and habitat issues.

“It’s really important that people of the surrounding communities continue to advocate for their resources and make sure that the development that occurs and whatever comes next are still protective of water quality and the character of the surrounding communities.”

Much of the work to delist the AOC was accomplished in 2012 when the Muskegon Conservation District completed the White Lake AOC Habitat Restoration Project. Through the project over 8,000 linear feet of shoreline was improved, over 38 acres of wetland habitat were restored or created, nearly 15 acres of riparian and upland habitat was restored, nearly 52,000 cubic yards of shoreline/submerged debris was removed, and 500 lineal feet of sheet-pile seawall was removed.

Also, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) funded the dredging of what was declared a “dead zone” in the lake due to pollutants having harmed the lake bottom and its habitat for benthos and other aquatic life.

Further, using $2.5 million in GLRI funds, EPA removed contaminated sediment along the Tannery Bay shoreline in White Lake. This contaminated sediment was largely the result of dumping of chemicals in lagoons near the lake by Genesco/Whitehall Leather Company (“the Tannery”). The company used chemicals to soak leather hides in to remove hair from them.

There was also earlier work that helped lead toward the AOC’s eventual delisting. After an investigation of the tannery in 1995, in 2002 the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and Genesco, Inc. paid to remove 91,000 cubic yards of contaminated sediment from the lake near their outlet discharge pipe. In 2003, Occidental/Hooker Chemical dredged 12,000 cubic yards of contaminated sediment from the lake near their outlet discharge pipe.

“The site of the former tannery was purchased by a developer who had plans to build condos and a marina, potentially a restaurant, and a beach area,” says Riley. “He was trying to get some interest from potential investors and buyers for those condos.”

In 2005, another company, Koch Chemical, agreed to install a new well for the City of Whitehall due to groundwater contamination overlapping with the city’s “groundwater protection area”.

“Residents really like the small town charm of the nearby communities like Whitehall and Montague,” Riley says. “Everybody wants to see economic development and opportunities for employment and a better local economy, but at the same time some people are weary of too much development too quickly and changing the character of the small town charm that those places have. I think a lot of communities struggle with maintaining that balance between keeping the character of the communities they fell in love with and having opportunity for growth in the future.

“The AOC program was able to take care of the worst of the worst problems,” continues Riley. “We just kind of got them back to a condition that is comparable to other communities in similar geographic areas. We didn’t solve all their problems by a long shot.”

This series about restoration in Michigan’s Areas of Concern is made possible through support from the Michigan Office of Great Lakes through Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.