MAPAS: How better information makes better communities

In the quest for better communities, knowing is half the battle, and MAPAS and Community Profles are making the right information available locally. J. Rae Young sits down with Jeremy Pyne to find out about the tools West Michigan is using to build tomorrow's neighborhoods.

Jeremy Pyne, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Manager at the Community Research Institute (CRI) and the project lead for the MAPAS and Community Profiles websites, states what most might think when they hear about his mapping websites: “I don’t know how many times I’ve heard, ‘Haven’t all the maps already been made? What else is there to make?’” After having that thought, the next thing most people would likely do on the website is to look-up their own address. “Every time somebody looks at a map, the first thing they do is look for their house to see what area they fall in,” says Pyne.

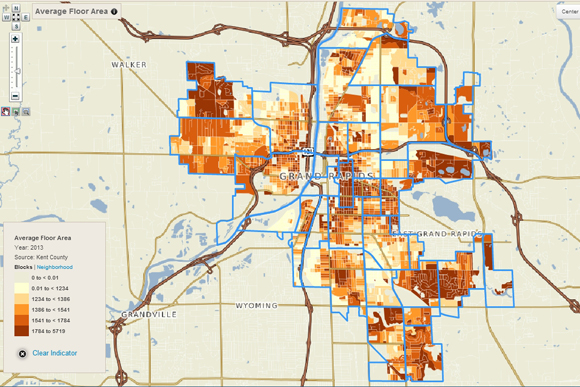

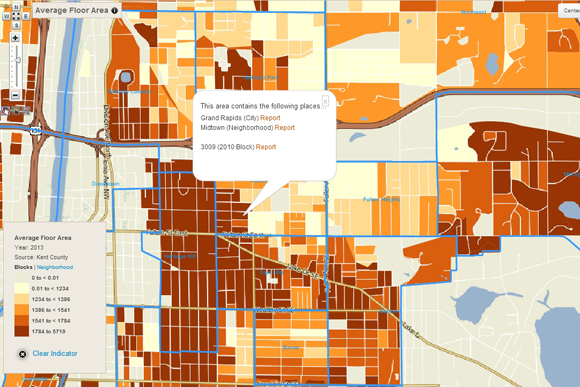

MAPAS and Community Profiles are web-based, interactive mapping tools aimed to make information more readily available to foundations, nonprofit groups, government, media, businesses, and citizens at large. With MAPAS 2.0 and its more recent companion, Community Profiles 2.0, anyone can build and layer maps around their own topics of interest, including population, housing, births and family health, education, employment, voting, crime, transportation and more. In other words, it’s like Google Maps for social indicators and variables in West Michigan.

MAPAS allows users to visualize information patterns across multiple geographies and down to a block-by-block level. “Unlike a table full of numbers, people can really relate to maps,” says Pyne. “That’s kind of how you identify place. You know where you are by the neighborhood you’re in.” Access to this kind of social mapping is relatively new, and Pyne has followed it in the course of its development through technology.

With the advice of an advisor, Pyne took his first geography class as an undecided undergrad at Grand Valley State University in 1999 and was enthusiastic right away. “As soon as I took that first class I enrolled as a major,” he says. During his study, GIS was heavily based on what Pyne calls “dirt and water.” Most GIS programs were mapping sewers, water systems, and environmental aspects of cities. When the 2000 U.S. census was released, Pyne became interested in how that information could fit into an expanded mapping system. “One of the first major projects that I did was looking at population change all the way down to the [neighborhood] level within the county,” remembers Pyne. “Seeing what kind of population change happened between 1990 and 2000, and not just population change but what types of populations were changing in different areas of the county.” That was the first time Pyne applied GIS to the social sector and his project caught the eye of a professor in the public administration department — where he would later receive his MPA — who connected him with the Community Research Institute, part of the Dorothy A. Johnson Center for Philanthropy in Grand Rapids.

When Pyne started as a new intern at CRI in 2001, it was new to the field, too. At that time, CRI had just begun to incorporate social data into their mapping systems. All the maps they made were physical copies requested by clients, with those requests predominantly coming from nonprofits that had or were applying for grants to work with a specific community need — requesting maps of local schools, employment levels, or income and poverty. “When we first started, you had to do everything by hand,” recalls Pyne. “Now, the same stuff that we were doing back then, users can log on the website and do that on their own.”

The development process for this website included two rounds of community design sessions where more than 40 organizations and individuals were asked what they would like to see if they had access to an online mapping system. “The best way to figure out what information is needed is to talk to people in the community who know that area,” states Pyne.

Since its launch in 2008, MAPAS has only grown and improved. Pyne points out that the increase in technology during the past decade has enabled the MAPAS website developers to present a variety of data options for clients to use in customizing their needs. “Now, it’s really getting to the point [that if] you have your own information, you can put it in and map it,” Pyne predicts.

But the advances are not just all high-tech. Pyne also credits the success of MAPAS in the mid-sized city of Grand Rapids to CRI’s amicable collaborations here. “One advantage that you have is being able to build relationships with people that have access to that information that would be useful for a nonprofit outside of government,” he explains. “Because we’re a smaller city and because we don’t have some of those big city issues, we’ve been able to have those internal connections.” For example, CRI has had an ongoing and productive relationship with the Grand Rapids Police Department. In addition, Pyne acknowledges that the tools which MAPAS and Community Profiles use are constantly improving, thanks to the help of the nearby Dyer-Ives Foundation.

The MAPAS data library is always expanding as they continue to add new data sets, and CRI continues to have discussions with community members who still help them prioritize which data sets they add to the database. Currently, with the implementation of Community Profiles 2.0 , they are meeting with groups that have interests in information on housing, economics, and public health.

“It’s really community driven. Rather than us trying to figure out what the community needs on our own, we need that feedback,” says Pyne. “It’s really picking out what is the most useful information and having that available to people that need to access it.” Accordingly, in a high-touch way which only complements all the high tech, CRI enables the community to reciprocate with their own beneficial information, helping to make things better for both CRI and the clients it serves. To that end, CRI sums up its vision and commitment with this simple but profound statement: “Better information makes better communities.”

J. Rae Young is a passionate promoter of Grand Rapids’ dynamic local music scene, venues and businesses, and an advocate of cultural understanding. She has taught English locally and in Tanzania, Africa, and treasures personal growth through travel.

Photography by Adam Bird